Bringing a human touch to digital innovation in Europe: The artist in the science lab, Maya Jaggi, δημοσίευση Le Monde diplomatique [1/2023]

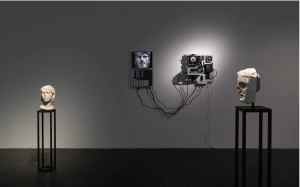

Trevor Good, courtesy of the artist and Alexander Levy Gallery, Berlin

When climate change protesters hurled tomato soup at Van Gogh’s Sunflowers in London last October, they shouted, ‘What is worth more? Art or life [and] the protection of our planet?’ One Just Stop Oil activist claimed the protests kickstarted the conversation ‘so that we can ask the questions that matter’.

Whatever the publicity from these symbolic acts of vandalism, the implied opposition between art and environmental ethics is misleading. Artists have long been in the vanguard of raising public awareness of the fragility of nature. Judging by the fruits of a Europe-wide scheme to immerse artists in cutting-edge science and technology (roughly half these EU projects involve ecology) (1), the questions posed by this rising avant-garde are arguably more nuanced, profound and conducive to behavioural and political change than protesters’ shock tactics.

At the Bozar Centre for Fine Arts in Brussels last month, laboratory-like installations by Haseeb Ahmed, an American artist based in Belgium, warned of the pharmaceutical pollution of water through human urine — a counterpoint to the city’s landmark Manneken Pis fountain with its urinating cherub near the Grand Place. One of these, The Fountain of the Amazons (alluding to legendary female warriors), demonstrates unintended effects on aquatic life of contraceptive hormones entering the water system: an artificial vagina squirts a pill per day into a vat of orange urine in which a mutant creature floats as though plucked from a Hieronymus Bosch painting.

In a companion artwork, A Fountain of Eternal Youth, human growth hormones ingested for their putative anti-ageing properties are dripped via an IV tube into a circular pool whose mirror surface (evoking Narcissus) invites viewers to weigh the costs of their own habits and desires.

Ahmed’s artistic ‘scenarios’ convert research on large-scale phenomena ‘to a scale the body can experience, addressing our senses,’ he told me. His aim is not protest ‘art against pharmaceuticals, because it’s complex; we rely on them to maintain our quality of life. The pill brought social freedom for women, but it’s also affecting the androgynisation of fish. So I create machines to help us think together about our ambivalence.’

‘Thinking machines’

Ahmed’s intriguing, disturbing ‘thinking machines’ were part of a Bozar group show, Faces of Water, resulting from artists’ residencies with scientists and engineers around Europe to explore phenomena from toxins to melting glaciers. He worked closely with pharma companies, and also water treatment and public policy experts: ‘Because knowledge has become hyper-specialised, we’re trying to tie knots between fields, to understand the world we’re producing.’ While not without friction, these collaborations can spark dialogue. One company, he recalled, was ‘unhappy with an accusation in the press that they’re not doing enough, so they took out an ad to say what they are doing.’

Περισσότερα εδώ.